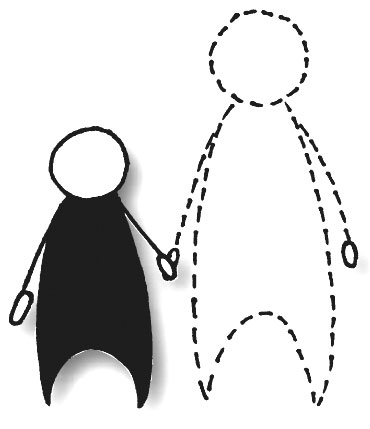

Illustration by Tamika Ono-Knight

Under federal law, parents typically have only 15 months to prove that they can safely reunify with their children. For parents struggling with addiction, that’s a short time to break the cycle of relapse and recovery. Yet research shows that children in foster care do better when they have parents or other biological family members in their lives. Here, LaShanda Taylor, associate professor of law at the University of the District of Columbia’s David A. Clarke School of Law, describes how some states are making it easier for parents and children to stay connected despite termination of parental rights (TPR).

Q: What rights do parents have to visit their children after TPR?

A: A lot of times, children don’t really understand why they are not allowed to see their parents anymore and this can be traumatizing. In some states, like New York, judges may allow continued contact when parents voluntarily relinquish their children. There also have been individual cases where judges have allowed visites after TPR, but most states do not allow it because of concerns that continuing the parent-child relationship will make children less adoptable.

If children are adopted, some states let adoptive and biological parents enter into open adoption agreements that may include visits. But in most states, it’s a voluntary agreement that is not enforceable by law. If adoptive parents move away or choose to end the visits, the law favors the adoptive parents in whatever decisions they make.

One promising approach states are trying in order to avoid TPR altogether is “subsidized guardianship,” which allows the court to give guardianship of the child to a relative or other individual. (This closes the child welfare case.) The guardian can receive a subsidy to care for the child up until the child turns 18, or 21, depending on the jurisdiction, but the parent retains the right to visit, to make educational decisions, even to petition to regain custody. Parents should talk to their lawyers about whether they have subsidized guardianship programs in their states.

Q: Can termination be overturned?

A: A serious problem is that of “legal orphans,” children whose parents’ rights have been terminated but who have not been adopted. We don’t know the number of legal orphans in this country, but we know it has grown since the passage of the Adoption and Safe Families Act in 1997, because parents’ rights are terminated more quickly under this law. Each year a child stays in foster care, the likelihood that he or she will be adopted decreases by 80%.

About a dozen states have passed statutes that allow children or their agencies (but not parents) to file for the restoration of parental rights if, after some years, the child has not been adopted. Even though parents can’t file for custody, parents can keep the foster care agency updated on any progress they make. If parents don’t know whether their children have been adopted, they can go to the agency or to the child’s court-appointed lawyer to try to find out.

Critics feel these laws encourage children and parents to hold on to false hopes that they’ll be reunited. But advocates say they allow parents who have stabilized their lives the chance to legally reunite with children. Sometimes these laws have come about because parents’ organizations rallied for them. Other times, the courts said: “We’d love to give this child back to his parent but the law prohibits us from doing that.” Many times, children still have an ongoing relationship with their parents, even if it’s not approved by the court.

Now is a good time for advocacy organizations to push for laws to restore parental rights after TPR, because more and more states are recognizing that birth families can be a resource for children who are unlikely to be adopted. It’s really not in the best interest of children to have no parent at all.