WHO ARE PARENTS AFFECTED BY CHILD WELFARE?

Most parents whose children enter foster care grew up in painful circumstances themselves. In New York City, where Rise is based, most affected parents are poor, single mothers of color living in distressed neighborhoods. Recent research on NYC mothers with children in foster care found that 54% met the criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Research suggests that 25%-40% of mothers with children in foster care grew up in foster care themselves.

Parents who come to the attention of the child welfare system have often demonstrated incredible survival skills in their efforts to provide for themselves and their children despite serious emotional and material obstacles. As many parents have described in Rise, their resourcefulness and determination to change family patterns have often kept them and their children safe for many years.

At the same time, breaking negative family patterns can be extremely difficult. As children, many of these parents faced threats they were powerless to control and developed ways of coping— dissociating, numbing pain with drinking or drugs, flying into a rage—that were useful in the short term to manage abuse they could not escape. When stress escalates in a precarious family and parents feel under threat once again, these same coping mechanisms can kick in and put children at risk.

One crisis can lead to another, and that's often when the child welfare system enters parents' lives. Story after story in Rise has documented family crises precipitated by the loss of a spouse or partner; a helpful family member becoming too frail to continue assisting; a job loss or housing loss; or a traumatic incident, such as sexual assault.

Generational repetition of family patterns is typical for all parents. (“I am sounding just like my mother.”) For parents with very painful family histories, however, these patterns can be terrifying. “Going into adulthood I prayed and promised myself that I wouldn’t continue the cycle," one mother wrote in Rise. "But the problems I wanted to run from consumed me.”

POVERTY, RACISM AND TRAUMA

Children of color—especially black and Native American children—enter foster care at higher rates than white children and stay in care longer. Racism contributes to unequal outcomes at every level in child welfare. Research in multiple jurisdictions has found that, even when cases are similar, families of color are treated differently than white families.

Poverty also plays a significant role in determining who enters foster care. In some jurisdictions children can be removed simply because of inadequate housing. More invisibly, poverty contributes to child welfare involvement because poor families are far more likely to: give birth in public hospitals, where testing for illegal drugs is more common; access health care at hospitals or clinics where doctors don't come to know their families and are quick to call in reports; send their kids to under-resourced public schools that are more likely to call a hotline than provide referrals to community supports; receive mental health care through inexperienced clinicians; and come into more frequent contact with "mandated reporters" through shelters or government offices. All of these contacts with under-resourced institutions and professionals make poor families less likely to find the help they need in a crisis and more likely to be reported on a suspicion of abuse or neglect.

Community violence, historical trauma and the scarcity of trauma-focused services also contribute to child welfare involvement. Parents with children in foster care report extremely high levels of trauma exposure and PTSD. In particular, the vast majority of mothers who have written for Rise report histories of sexual assault. Only recently have child welfare systems begun to understand, screen for, or offer trauma-focused treatment.

Misunderstanding of trauma, misdiagnosis of trauma-based mental health issues, and the routinely punitive and shaming treatment of parents that can result from bias and from frontline staff becoming overwhelmed by trauma exposure themselves all combine to make it much more challenging for parents to access needed services and support.

WHY STORIES?

In child welfare, it’s often considered either difficult to get parents to tell their stories or dangerous to let them. Parents stay silent about the roots of family crises, fearing that their personal information will be used against them. Families and communities warn against “airing your dirty laundry.” Parent attorneys also must frequently advise their clients not to speak; the court process is often adversarial.

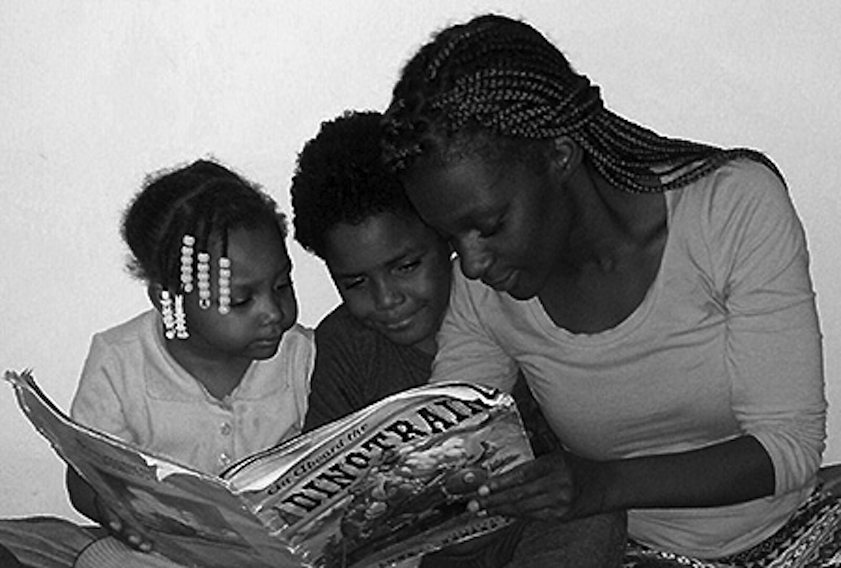

Yet it’s crucial that child welfare professionals better understand the parents and communities they serve. If parents are heard during an investigation, they will be less likely to suffer unnecessary system involvement. When intervention is necessary, parents who are listened to, supported and valued for their knowledge of their families are more likely to get connected to services tailored to their needs. When families are separated, all children want to return safely to their parents.

Rise's writing process draws on research around the therapeutic benefit of making an experience into a story, including the process of challenging and correcting that story. Yet it’s important to emphasize that Rise’s writing workshops are not offered as a direct service. Parents are motivated to join our writing groups because they want their stories to be heard. They have absorbed pervasive negative images of parents in the especially brutal child welfare cases covered by the media. They want their strengths, their efforts to care for and protect their children, to be recognized. Writing for Rise offers parents who so often feel put down and shut down the chance to speak up. It also reverses the roles for parents who have been the ones to need help; as writers they help others.

At Rise we have come to consider five elements as crucial to our work: privacy, safety, choice, control and voice. At a systems level, the child welfare system needs to get better at creating spaces for peer support and parent leadership. At a practice level, it’s crucial that child welfare professionals get better at drawing out parents’ stories. To accomplish this, courts and agencies will have to get better at not using parents’ revelations against them. They will have to find ways to listen to parents and to offer parents privacy, safety, choice, control and voice.

"WITH EVERY STORY I WRITE, I'M LEARNING WHAT IT TAKES TO BE ME"

My introduction to Rise was through the writing workshop at the Child Welfare Organizing Project. When I started, I was writing just to write. Then I found that writing was a way to gain insight into my life.

I never knew that writing words on paper would open up so many old wounds.

The first thing I discovered was that I’d suppressed a lot of what happened in my life. I remembered things my mother would say. Events that I thought I put behind me. Looking at my life on paper made it so real.

With every story I’ve written, I've learned more and more about who I am as a person and what it takes to be me.

For me, Rise has been and is a place of hope and support.

My writing has allowed me to see that, as much as I tried to be different from my mother, we are more alike than I care to admit. At times I yell too much, like my mother did. I tend to impose my ideas on my children. But I also come from a place of love and support.

Through my writing, I’ve realized that, in my mother’s generation, they thought that showing toughness was showing love. And that my mother did love me.

Now I make more of an effort to be more affectionate, and not be so judgmental. To be more involved with my children, and more aware of what I say and do.

“I CAN LET SOMEONE KNOW WHAT'S HAPPENED IN MY LIFE WITHOUT BEING JUDGED OR BLAMED"

For over 20 years, I was isolated. I was afraid to speak about what I’d been through or how I felt. I didn’t think people would listen. In the past I was blamed and judged.

When I did try to speak about what had happened to me, I re-lived the pain and would cry.

I joined Rise in 2008. I love to write and I wanted to put my stories on paper.

The editor, Nora, always asked, “Why did you say that?” “What did you do after?” and “How can you change it?” I would think, “Why is she asking me so many questions?” I had to realize that the answers made my story fit together.

At first, I wasn’t coming in as much. I avoided coming in because I was afraid of questions that I wasn’t ready to answer. It would be weeks at a time before I saw Nora again. Little by little I showed up more often.

Nora was very patient with me and gave me time. She didn’t rush me or give me a time limit. It made me feel comfortable.

And little by little, I was no longer crying every time she asked me those questions. I learned that you can let someone know what has happened in your life without being judged or blamed.

Not long ago, Nora asked if I would speak on a panel at the Bronx Family Court, about trauma. Just saying yes made me nervous. But I wanted to break free from my shell.

When I got there, I saw there were a lot of people in the room – at least 50 people – and I felt overwhelmed. Knowing they were judges and lawyers made me even more nervous. My stomach began to hurt. I thought I would stutter or mess up.

When it was my turn to read, I told myself, “Just imagine you’re speaking with Nora, alone in the room.” I didn’t look up. It was hard, but as I continued to speak it became easier. I became more confident. I felt that I could speak without fear to all of those people.

I had said that I wouldn’t answer any questions, but when the time came for the audience to ask questions, I answered the first one!

At the end of the panel, I felt relieved. I felt we made an impact on the lawyers and judges because they asked questions and they invited us to speak again.

Speaking at the conference turned out to be a good experience. I did it! I’m glad I did.

“MY VOICE CAN MAKE A CHANGE"

When my depression kicks in, I don’t bathe and I barely eat. I just stay in my bed and sob and be mad for reasons I don’t even know.

Last winter I was depressed for about two weeks and missing work at Rise because of it. For the next issue of the magazine, I was supposed to interview a professor at Harvard. The deadline was quickly approaching. My editor, Nora, called to see if I was ready.

Instead of telling the truth, I told her I had a cold. I thought that if she knew I was depressed, she might not want me to work for her anymore. What if she believed that people who have bipolar can’t hold a job? My safe haven at Rise would be lost.

But Nora was like, “I’m depending on you, Pia!” She suggested we do the interview by phone. I could call in from home.

I was shocked. Despite all of the obstacles I was throwing up, my editor still wanted to find a way for me to work. I felt needed, respected, cared about.

‘Find a Quiet Place’

The day of the interview, Nora called me about 45 minutes before. I lay on the couch and stared at the ringing phone, reading her name on my screen. “Are you ready?” she said, “Find a quiet place in your house and close the door. You’ll be fine.”

And you know what? The interview went smoothly. I had read the professor’s book – about poor fathers – and he actually responded well to me asking him questions about my life that related to his book.

After the interview, I felt successful. I was glad Nora gave me the courage to push past my depression and get the job done.

Skills and Confidence

Rise has given me work experience and confidence. I’ve learned administrative skills. I’ve also sat on panels and done presentations in front of dozens or even hundreds of people. The skills that I’ve learned from Rise have allowed me to feel like what I think matters and my voice can make a change.

See that’s what Rise is all about. Rise gives parents like myself the courage to believe in ourselves and be who we are. No judgment. Rise listens to us and believes in us, as people and as parents.